Carl Sandburg: Impact and Legacy

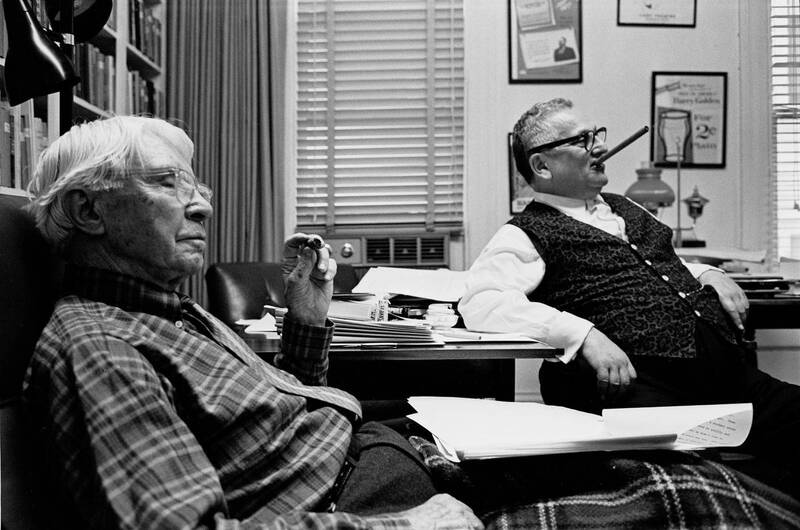

Sandburg made a lasting impact as a writer, despite some critics arguing that his lack of stylistic development should exclude him from the history books. Sandburg is a somewhat rare example of an artist being widely celebrated during their lifetime, rather than after their death. Fanny Butcher, literary editor for the Chicago Tribune and lifelong friend to Sandburg, wrote that the author’s “seventy-fifth [birthday in 1953] was a national occasion, with the Swedish Ambassador bringing greetings from the King of Sweden and the highest of that country’s decorations, Commander of the Order of the North Star, which everyone expected was a presage of the Nobel Prize” [9].

Throughout his life, Sandburg earned a number of awards in recognition for his work. He won a special Pulitzer award in 1919 for Cornhuskers, his second book of poems, as well as two later Pulitzer Prizes in 1940 and 1951 for Abraham Lincoln: The War Years and another volume of poetry (Complete Poems), respectively. He was also honored as the Harvard Phi Beta Kappa poet in 1928. Despite being highly celebrated, Sandburg was never awarded the Nobel Prize. When Hemingway was chosen as the recipient in 1954, “he told reporters that it should have gone to Sandburg” [10].

He was recognized by a number of other organizations as well, outside of the literary sphere. Perhaps most notably, Sandburg was the first white man to be awarded the NAACP’s Silver Plaque award in 1965. A book compiling Sandburg’s coverage of the Chicago race riots, as well as his general journalistic coverage that never shied away from Chicago’s racial climate and dedication to America’s working people, made him an important supporter of the fight for civil rights.

Sandburg enjoyed the success of his creative work during his life in Chicago before retiring to North Carolina in 1945. He lived there with his wife, daughters, and their families. He continued writing, albeit on a much smaller, more private scale, until his death in 1967. In 1968, his family members gave Connemara, their home in North Carolina, to the National Park Service. Five years later, it became a National Historic Site and can still be visited to this day. Sandburg’s historic home represents the rest of his work in a way—Sandburg's writing is accessible and personal. He is remembered as a passionate writer, who wrote of and for the people.

[9] Fanny Butcher, Many Lives—One Love (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), 381.

[10] Allen, “Carl Sandburg,” 5.