Carl Sandburg: Journalism and Poetry

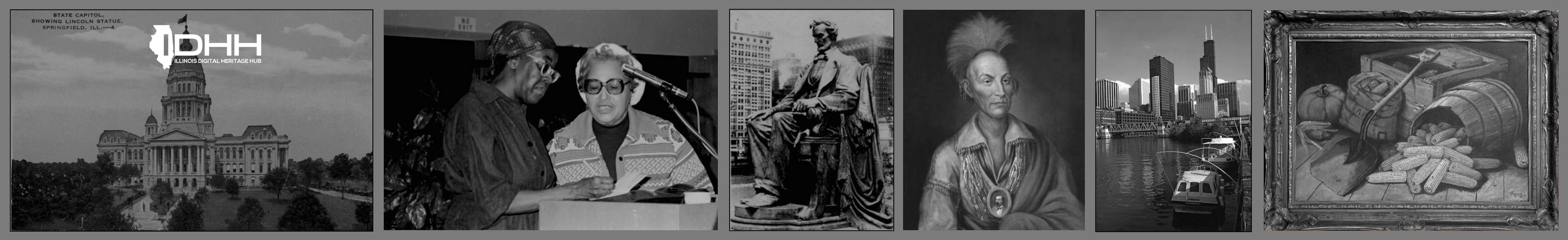

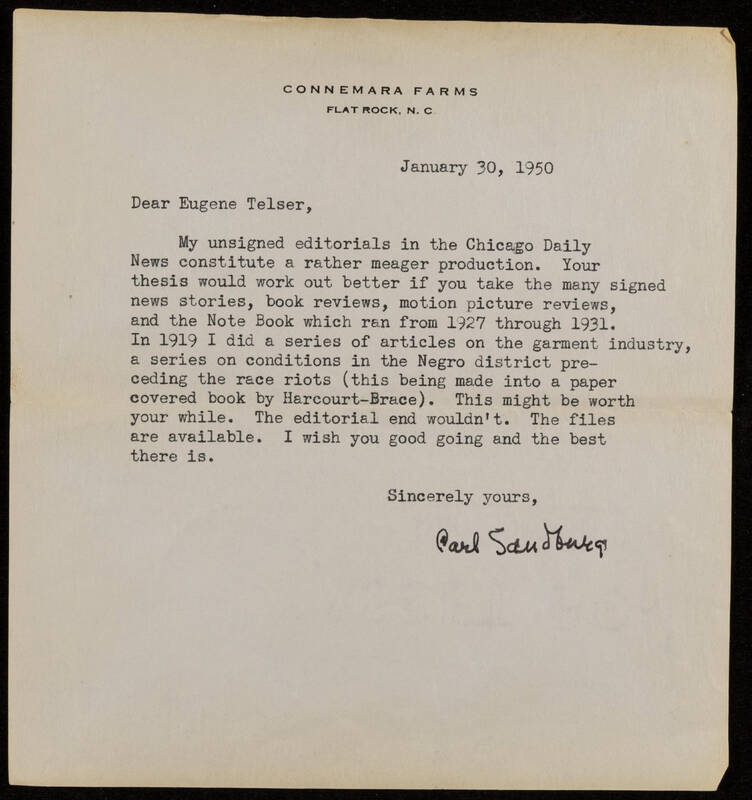

After Milwaukee, Sandburg and his family (which now included himself, Lillian, and the first of their three children, Margaret) moved to Chicago in 1913; he continued to work in journalism, although it was not always easy. Newspaper strikes and staffing changes made Sandburg move from paper to paper, but when he finally landed a job at the Chicago Daily News, he stayed there for the next fifteen years. During this time, he also began working on poetry when he had spare moments. In both his poetry and his journalistic writing, Sandburg paid attention to the lives of everyday people. Sandburg was a staunch supporter of civil rights, which is not a surprise, given his life experiences. One of Sandburg’s biographers wrote that “He grew up in a household where Swedish was the first language and explored the American heartland in search of his native tongue. In the process he became the passionate champion of people who did not have the words or power to speak for themselves” [2]. Sandburg notably wrote about race in Chicago, and covered the city’s 1919 race riots as well.

It was in 1914 that Sandburg’s first non-journalistic writing was widely published. He had submitted poems to Poetry, and to his surprise, he was not only published, but also received the Helen Haire Levinson Poetry Prize as well. These successes attracted the interest of publishers—after seeing Sandburg’s poems in the magazine, Alfred Harcourt supported the publication of Sandburg’s first book. Sandburg and Harcourt continued to work together for multiple other publications. Sandburg’s first book, entitled Chicago Poems, was released in 1916. Despite the faith of publishers, Chicago Poems was not entirely critically acclaimed; many did not understand or try to understand what Sandburg was doing. However, there were positive reviews, including one by Fanny Butcher, literary editor for the Chicago Tribune, in her popular Tabloid Book Review.

With regard to Sandburg’s poetic style, he did not try to follow any rules or write poetry in pre-established forms. Sometimes his work rhymed, but most of the time it did not. Sandburg’s seemingly aimless wandering during the beginning of his life ended up having a profound impact on his work and its style. Scholar Gay Wilson Allen writes of Sandburg and his contemporaries (Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, and others), stating that “their attitude toward human experience was realistic, the subject of their fiction and verse the life of ordinary people, and their style shaped by the idiom and rhythms of mid-American speech” [3]. Sandburg was dedicated to honestly showing the world he knew in his work. In his poem “Chicago,” he wrote of the city’s ugly side as well as its triumphant one: “Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning” [4]. Sandburg was celebrated for his emotional and raw portrayals of real life, but he was often criticized (sometimes by other poets) for not being more poetic. However, what rankled some critics appealed greatly to others, as Sandburg received several major awards, including multiple Pulitzer prizes, for his poetry (and other writing) over the years.

[2] Penelope Niven, Carl Sandburg (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1964), xviii.

[3] Allen, “Carl Sandburg,” 7.

[4] Carl Sandburg, “Chicago” (Chicago: The Poetry Foundation, 1914), 191-92, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20569994.