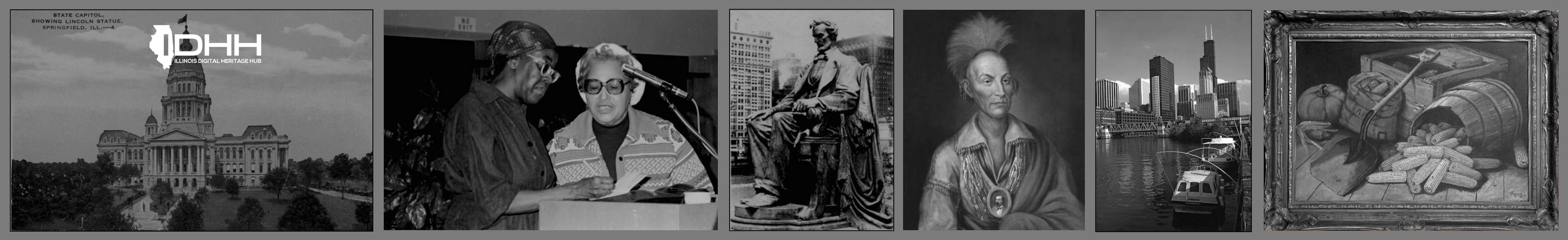

A Century of Progress International Exposition: In the Shadow of 1893

While Rufus C. Dawes and the other organizers envisioned a Fair which enticed fairgoers with a glimpse of the bright future ahead for a depressed America, the Century of Progress in 1933 reinforced many of the mistakes and grievances of the World’s Columbian Exposition 40 years before. Similar to that first Chicago World’s Fair, the Century of Progress included a Midway area offering popular entertainments and vendors that traded on the exoticism and otherness of various groups. The Midway in 1933 included a “freak show” featuring physically challenged or different individuals with names and titles to exaggerate or highlight their difference, a small city run completely by people with dwarfism called the “Midget Village”, and Ripley’s Odditorium, which boasted such curiosities as a woman who could swallow her nose. Attractions such as these highlighted the darker side to the notion of progress presented at the Fair, one that raised the White, Western scientific norm as the pinnacle of progress.

Black Americans found themselves also shut out from the Fair’s ideal of progress in 1933. The Fair authority officially sponsored no exhibits concerning ethnic or racial progress throughout the run of the Fair, and harmful stereotypes such as that of the “Mammy” were often used in advertising. Indeed, actress Anna Robinson would portray the infamous character of Aunt Jemima in the General Exhibits Group pavilion of the Fair. Discrimination of people of color at the Fair was so frequent, the Chicago branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People documented handling hundreds of legal cases, winning over $5,000 from Fair organization and concessionaires in judgements.

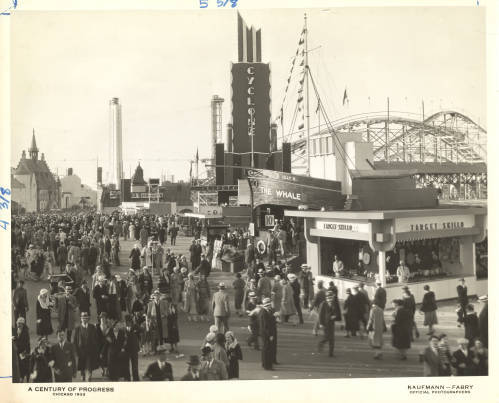

Even in this climate of prejudice, independent groups like The National De Saible Memorial Society created spaces for African Americans to see themselves and their history represented truthfully at the Fair. Founded by Annie E. Oliver in 1928, the Society successfully produced a reproduction of Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable’s cabin at the Fair. Approved just four months before the opening of the Century of Progress and situated on the Midway by other pioneer sites, the reproduction was designed by the African American architect Charles S. Duke. A space defined by the community itself, the cabin attested to the fact that Chicago’s first settler, founder, and entrepreneur, Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable, was indeed a person of color.