The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893: The White City, Midway Plaisance, and Ferris’ Wheel

Attractions and exhibit halls at the World’s Fair were spread across the main Court of Honor, the Midway Plaisance, and the remaining landscape of the fairgrounds. There were fourteen main exhibit halls that comprised the "Great Buildings." Some were arrayed about a huge lagoon, while others were part of the Court of Honor, surrounding a giant reflective pool known as the Grand Basin, on which gondolas skimmed. The gleaming white exterior of these Great Buildings, largely constructed of a mixture of plaster, cement, and hemp, projected an air of permanence and grandeur befitting the vision of perfection and civilization the White City sought to convey.

The Great Building furthest from the central Court of Honor and closest to the raucous sights of the Midway Plaisance was the Woman’s Building. The only building designed by a woman architect, 21-year-old Sophia Hayden of Boston, Massachusetts, the Woman’s Building was devoted to exhibits and arts by women creators, all of which were selected by the all-woman 117-member Board of Lady Managers of the Fair. Organized entirely by the Board of Lady Managers of the Fair, the Woman’s Building featured such areas as a library completely stocked with titles by women authors, a Children’s Building displaying the latest advances in child-rearing and education, and exhibits showing women’s achievements in arts, science, and industry. Activists such as Susan B. Anthony decried this separate but equal stance, advocating for equal representation of women throughout the World’s Fair’s buildings; they even established a rival group, the Queen Isabella Society, to petition for women in regular positions of World’s Fair management. Others such as the wealthy Chicago businesswoman, socialite, and President of the Board of Lady Managers, Mrs. Bertha Palmer, saw it as a triumph that women had a space at the Fair at all.

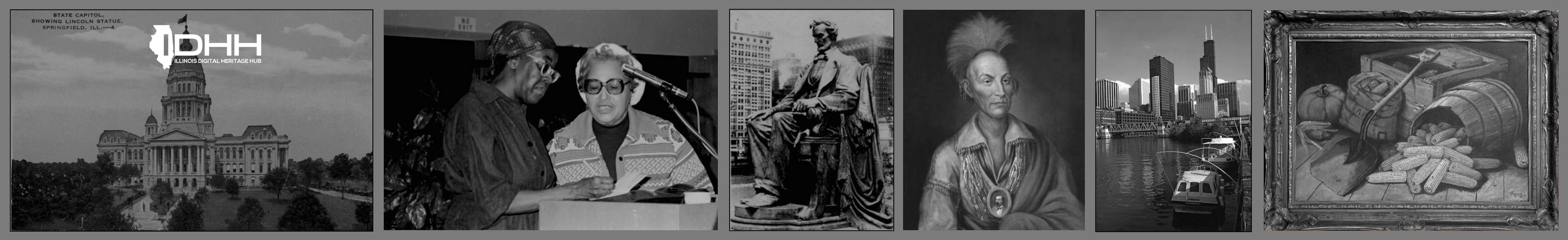

Further west, visitors would move away from the white facades of the Great Buildings and find themselves amongst the revelry of the mile-long Midway Plaisance. A cacophonous stretch of attractions by private and international exhibitioners, the Midway was the first of its kind to be seen at a World’s Fair and an irresistible draw for many fairgoers. Visitors paid extra to view Algerian and Tunisian villages, take a walk down “A Street in Cairo,” and watch “Esquimaux” individuals go about their daily lives as though they were still in the Arctic regions. Modeled after the so-called ethnological villages presented at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris, these recreations on the Midway Plaisance were presented under the guise of anthropological inquiry with Frederick Ward Putnam, a leading ethnologist of Harvard, overseeing the area. In truth, guests of the Fair flocked to the sights along the Midway Plaisance to ogle at the unfamiliar peoples there and experience the stark contrast between the pristine civilization of the White City and the exoticism of “savage” cultures from around the world.

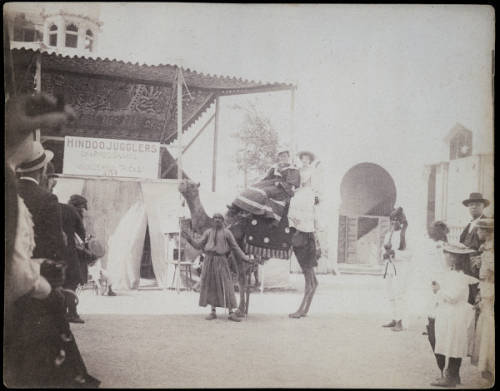

Rising above the throngs of the Midway Plaisance was the crown jewel of the attractions outside the White City—a Ferris Wheel. Early in the planning for the World’s Columbian Exposition, Daniel Burnham and other organizers sought a monument that would exceed the spectacle of the Eiffel Tower, the centerpiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Conducting a nation-wide contest, Burnham solicited ideas of what could be built that would outdo the Eiffel Tower. The best of the suggestions, another tower like the Eiffel, did not satisfy Burnham, so he conducted a second round of appeals in 1892. Ultimately, he was won over by the entry from George Ferris, a civil engineer born in Galesburg, Illinois: a giant rotating wheel that would carry 40 passengers in each of its 36 passenger cars. Though Ferris’ steel Wheel would not be ready for riders until six weeks after the opening of the World’s Fair in 1893, the Wheel was a hit amongst the many visitors who paid the 50 cents to rise about 264 feet in the air and peer at the Midway below.