Exhibit Contents

Traditionally, bibliographers and historians have overlooked women's contribution to the history of book production as being minimal, and tied to the work of their husbands. While a few especially prolific women printers have been recognized, most with shorter careers have been dismissed. This exhibition, researched as part of an independent study and project for LIS 301 is an attempt to recognize and rectify their exclusion from directories of printers, bibliographies, and histories of printing.

Since the advent of printing around 1450, women have actively participated in the printing trade throughout Europe. Usually, women entered the trade through marriage: by marrying a printer, or by being a printer's daughter, carrying a share in a printing house as a dowry. Most women were married at quite a young age to older, established printers ("freemen" in the British system) whom they then assisted in running the printing shop. These older men would soon die after years of tough labor, leaving their young widows in possession of the printing house until they remarried, often to apprentices within the same shop. This "syncopated marriage rhythm" is often visible in the spurts of printing by women between husbands. While women were not legally allowed to own printing shops on their own, as widows they were allowed to continue the business until they remarried, or their sons came of age to take over.

In Great Britain, the Company of Stationers, chartered in 1557, controlled all aspects of the printing trades, including apprenticeships, succession of printing houses, and, most importantly, entering of copyright to prevent piracy. While early in the history of the Company, certain printers had monopolies on frequently printed books such as bibles and almanacs, in later years, these works were released from perpetual copyright by one printer, and jobbed out to many different printers, as the market demanded them. Since the Company had provisions for widows and orphans, it is quite common to see items printed by women "for the Company of Stationers"-items which, through publication, literally kept the print shops run by widows afloat.

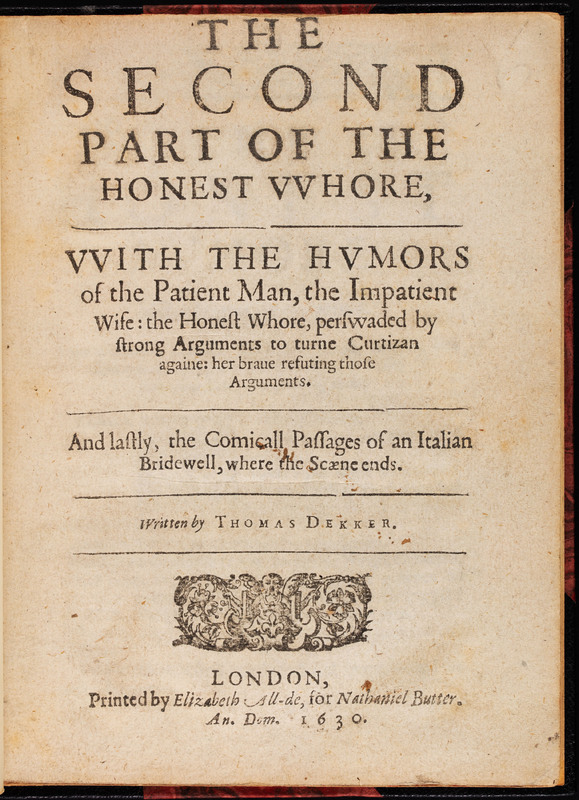

In addition to those items jobbed out by the Company, certain types of publications were likely to be produced by women. These included devotional literature, books on moral instruction, educational books (grammars, histories, and the like), books on household issues, and popular literature. According to Suzanne Hull, these are exactly the types of books that were aimed at a growing number of feminine readers. All of these genres are represented in this exhibition. Women booksellers and publishers have been included, since these functions were not necessarily separate before 1700.

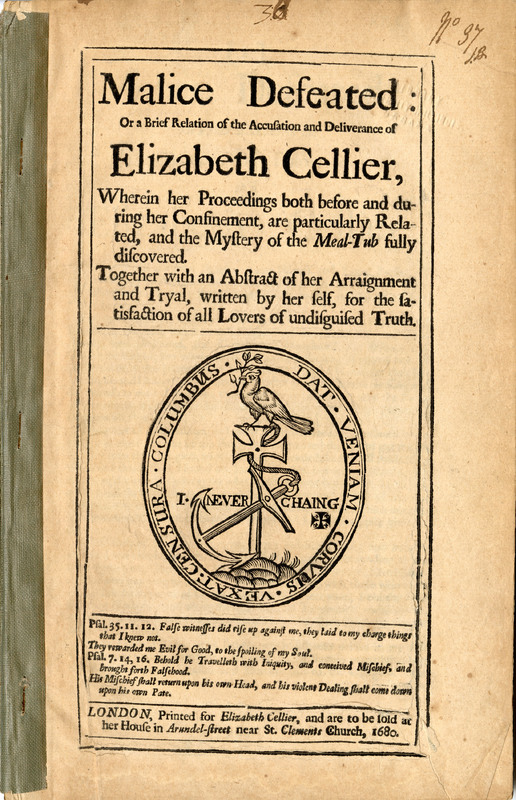

That is not to say, however, that women did not produce works outside of these genres. Many women were involved in more complicated aspects of printing, including printing maps and sheet music. While most widows continued where their husbands had left off, some women, especially during the Civil War in Britain, were active in producing or selling political pamphlets, arguing either for or against both Protestantism and Catholicism. They also addressed social issues of their own accord. Some "rabble rousers" were even censored, put on trial, and jailed for their presswork. The books shown here are only a representative percentage of the early works produced by women that are part of the Rare Book and Special Collections Library's holdings. A growing database of nearly 600 titles produced by women is now available for consultation here in the RBSC Library.

Introductory images

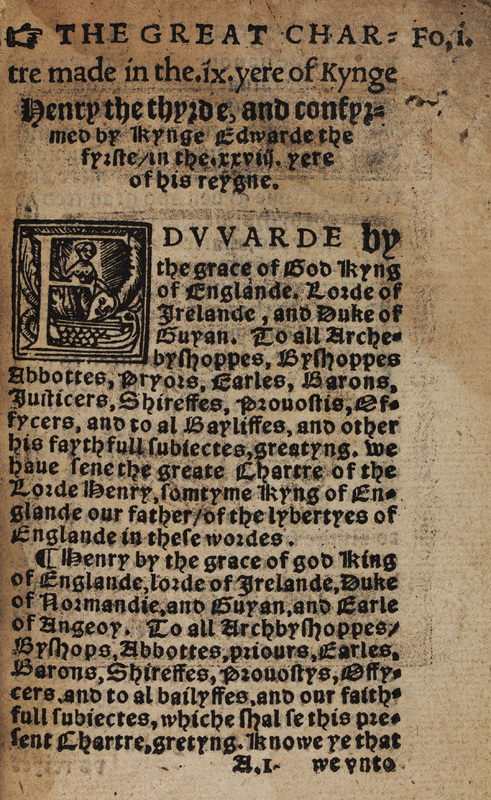

This book is one of the earliest in the collection printed by a woman. Elizabeth Redman, originally Pickering, was the widow of Robert Redman (fl. 1523-1540). She only printed a few works before remarrying, but is of note because she is one of the earliest documented widow printers in Great Britain. Robert Redman was a successor of Richard Pynson, (fl. 1492-1530); they were rivals while Pynson was alive, since Redman not only issued pirated editions of Pynson's works, but adopted his "sign" (i.e. address) as well.

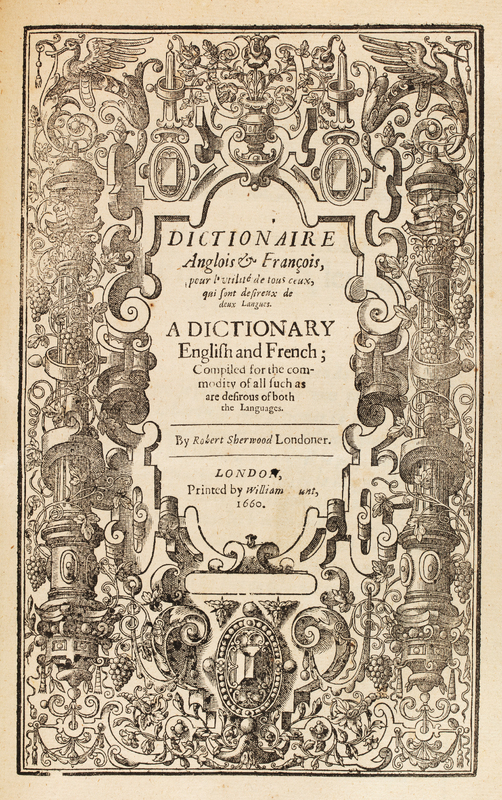

Susan Islip (fl. 1641-61) was the widow of Adam Islip (fl. 1591-1640). Widows often printed "useful" books such as this dictionary, which is less extensive than the dictionary with which it is bound.

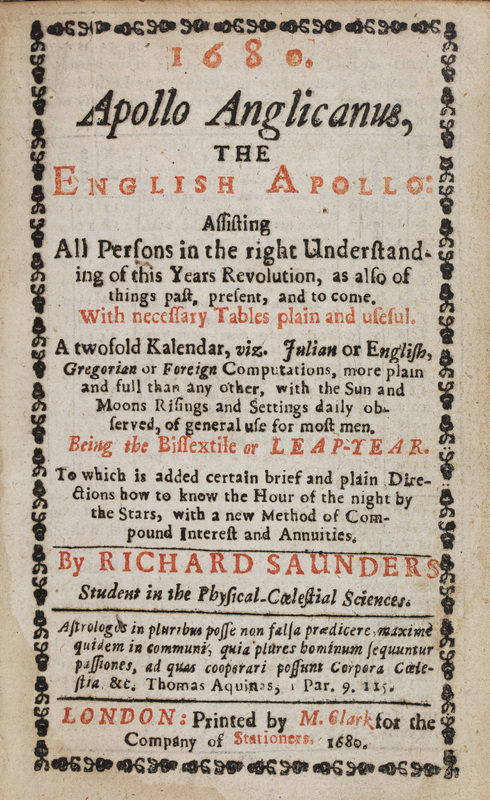

This almanac may have been "jobbed out" by the Company of Stationers to Mary Clark (fl. 1677-96), the widow of Andrew Clark (fl. 1670-78). Mary continued the business for nearly twenty years after her husband's death, and was quite prolific, printing almanacs, devotional literature, and the like, often for the Company of Stationers.

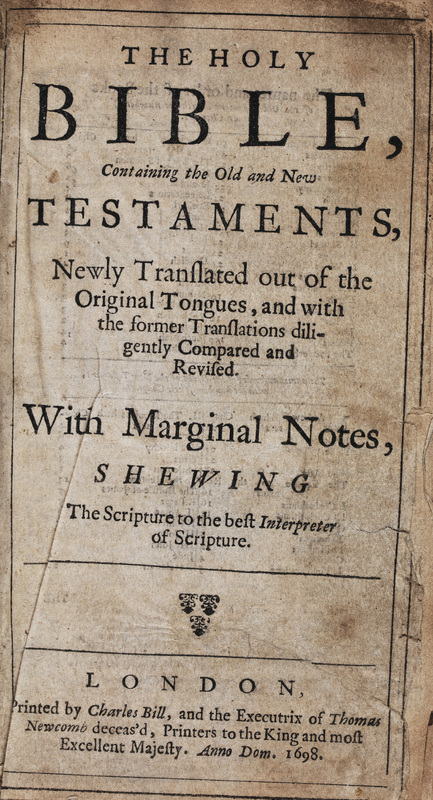

The executrix of Thomas Newcombe (fl. 1649-81) was his widow, Ruth (fl 1643-65, 1691-1700?) Newcombe was her second husband; she had also been widowed by another printer, John Raworth (fl. 1638-45). She continued the business from 1646 to around 1649, when she married Thomas Newcombe, who took over. In a 1668 survey, Newcombe's printing house was one of the largest in London. Newcombe was also a shareholder in the King's Printers. This closely printed Bible, produced after his death, was apparently a collaboration between the widow and Charles Bill (fl. 1687-1699), another of the King's Printers. According to Henry Plomer, Bill, although a shareholder in the King's Printers, never appeared to actually exercise the printing trade--which would mean that the production of the book was likely entirely directed by Ruth Newcombe.

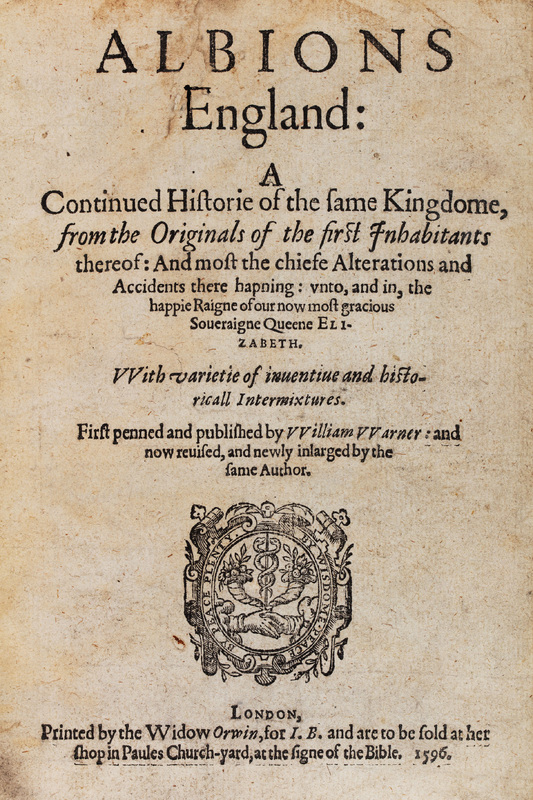

Joan Orwin married three different printers in her life: John Kingston (1553-84), George Robinson (1585-7), and Thomas Orwin (1587-93). She continued the business from 1593 to 1597, when it was taken over by her son, Felix Kingston. The text is one of the standard histories of the period. Thomas Orwin's device, used by his widow, is visible on the title page, with the motto "By Wisdom peace by peace plenty." The book was likely sold by Joan Broome (fl. 1591-1601), widow of William Broome (1577-91); this is an early example of women working together in the printing trades.

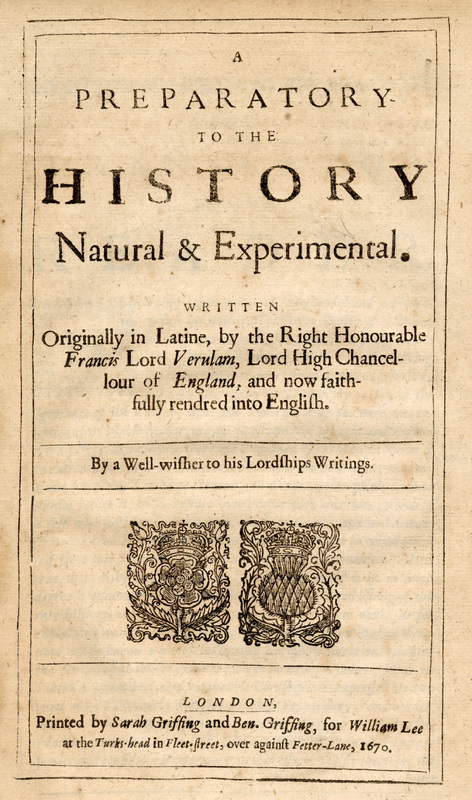

The Griffins were a printing family, part of a house originally founded in 1590. Sarah (fl 1653-73) succeeded her husband Edward II (fl 1638-52). Edward II had printed in partnership with his mother, Anne (fl 1634-43), and later succeeded her His father, Edward I (fl 1613-1621) was also a printer. Bennet Griffin is probably Sarah's son, who later restricted himself to bookselling and publication, rather than being physically involved with the printing of works like Bacon's Sylva Sylvarum.

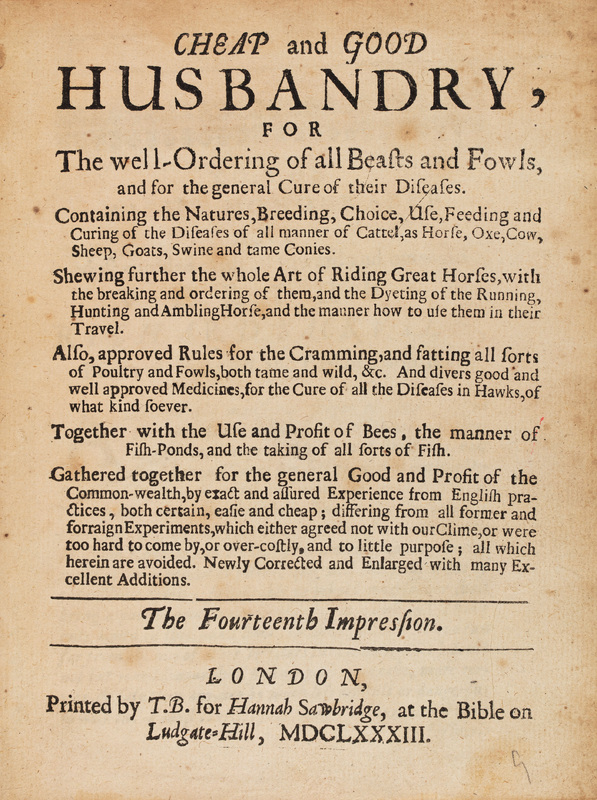

This popular "how-to" text on animal husbandry and other household uses was sold by Hannah Sawbridge (fl. 1682-86), the widow of George Sawbridge the elder (fl. 1647-81). Sawbridge was a partner in the King's Printing House, treasurer of the Company of Stationers for much of his life, and Master of the Company in 1675. He left behind a good deal of wealth to his wife, and was known as one of the greatest booksellers in England at the time. Hannah continued the (quite lucrative) printing business until his son took over.

Exhibit Contents

Acknowledgements

Chez La Veuve - Original Digital Exhibit (August—November 1998)

This exhibit was curated by Lynne M. Thomas, Head of the Rare Book & Manuscript Library, during her time as a graduate assistant.

Digital Exhibit Arranged by: Ben Ostermeier and Nora Davies