Exhibit Contents

Rabble Rousers

Women were not immune from the changing political climate of England in the 17th century. The works in this case are examples of women who were involved in the political battles of the day, from raising awareness of social issues, to being censored and put on trial for their beliefs. Officially sanctioned religions (Protestant or Catholic) changed rapidly during the Tudor and Stuart periods with the accessions of different rulers to the crown. In such a climate, an anti-Catholic or anti-Protestant tract could be grounds for imprisonment, depending upon who was on the throne at the time of its publication.

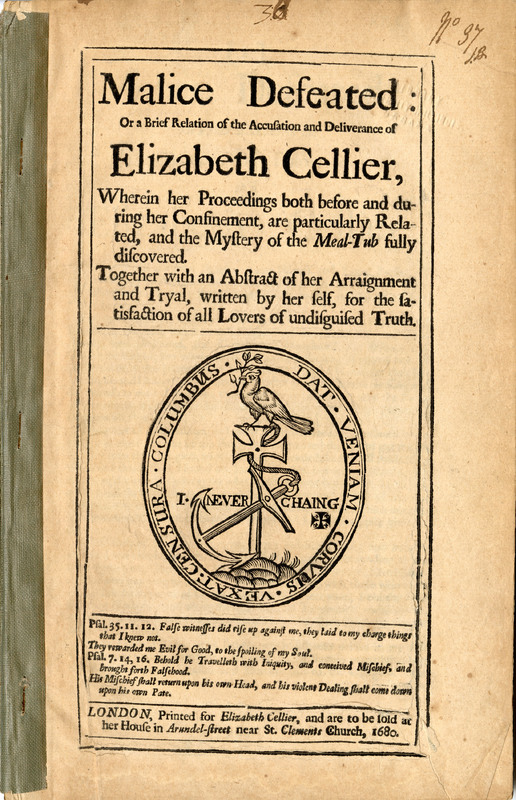

Malice defeated

Cellier, Elizabeth. Malice defeated; or a brief relation of the accusation and deliverance of Elizabeth Cellier. London: For Elizabeth Cellier, 1680.

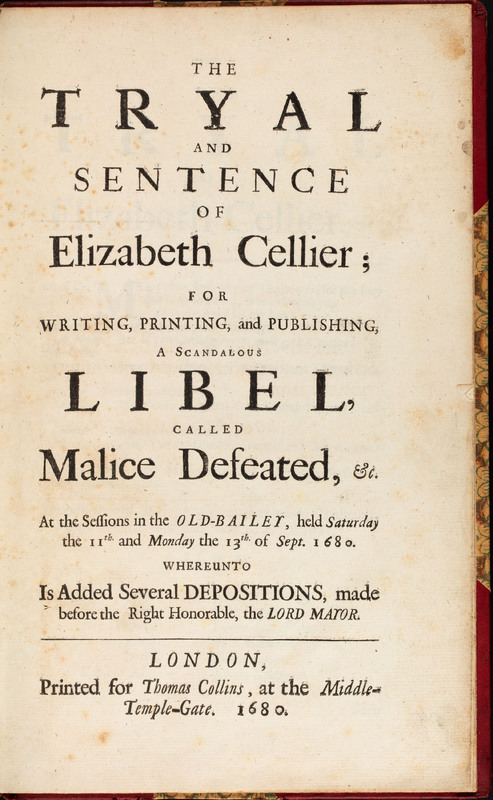

The tryal and sentence of Eliz. Cellier

Cellier, Elizabeth. Malice defeated; or a brief relation of the accusation and deliverance of Elizabeth Cellier. London: For Elizabeth Cellier, 1680.

Elizabeth Cellier was an ex-Protestant who wrote a narrative describing her aid to imprisoned Catholics, and the horrific conditions of Newgate Prison. The narrative was suppressed, and she was then put on trial for having published libellious material against Charles II. She was fined one thousand pounds and pilloried for several days at different locations. At each location, copies of her libellious narrative were burned. Malice defeated is part of the Baskette Collection, a collection of materials that were challenged or suppressed in some way for their content.

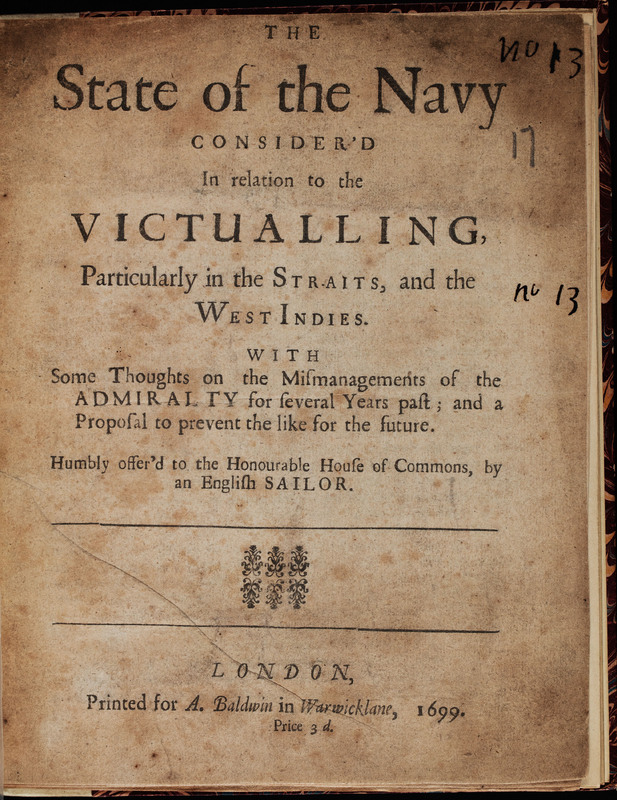

Ann Baldwin (fl. 1698-1711) was the widow of Richard Baldwin (fl. 1681-1698). While her husband was alive, Ann was active in the business, and controlled all of the accounts. It is likely that she also exerted some editorial control over what was published. The Baldwins were decidedly Whig publishers. Richard spent a good deal of time before the courts for his (their) "anti-Stuart, anti-French, anti-Papal" tracts and news-sheets," besmirching the names of James II and Louis XIV at every chance (Rostenberg 370, 372). His zealotry got him into a public brawl in 1681, fined in 1682, and jailed in 1690 (374, 378). Upon Richard's death, Ann continued to produce tracts, news sheets, satires, ballads and commentaries in the spirit of her husband (237 different publications over her tenure) (400). She was also very likely arrested in 1711 for her anti-Tory publications (402). Ann expanded upon her husband's single-mindedness, publishing a group of tracts, such as this one, that concerned social welfare--she was particularly concerned with the plight of English seamen, who had been abused by being served only rotten food.

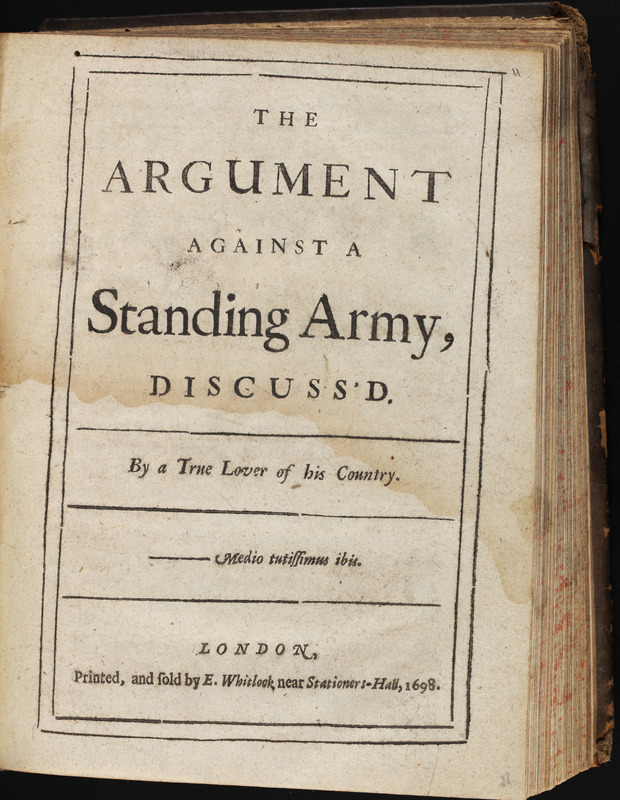

Ann Baldwin was not the only printer to take on social causes of her own accord. Elizabeth Whitlock (fl. 1695-99) succeeded her husband John (fl. 1683-95). The pamphlet shown here was printed in response to one printed by Baldwin, which is also bound into this volume. Because the topic at the time was so controversial (and in opposition to the King's views), many of the pamphlets in this particular volume do not list a specific printer. Whitlock, printing a pamphlet that sides with the King, was free to declare her involvement in the project.

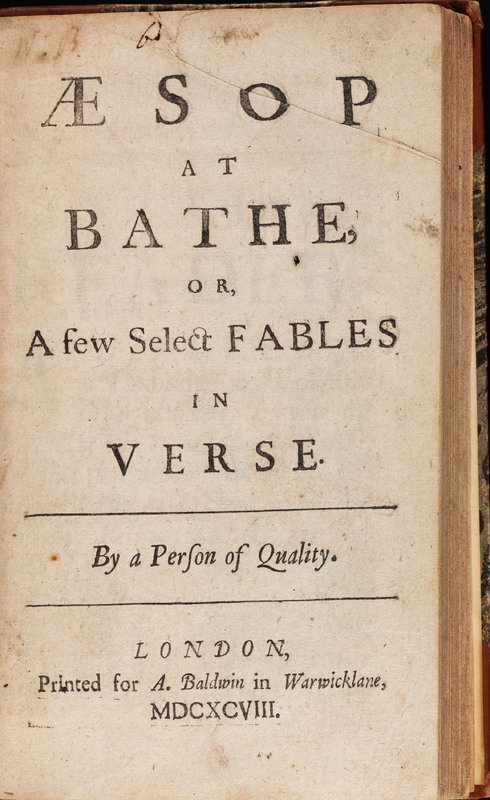

This volume is purportedly a collection of Aesop, but most of the fables do not resemble Aesop in any way, and are political commentaries instead, written in the style of Aesop's fables. Baldwin's pamphlet, shown here, is full of Anti-Jacobite sentiments. However, there is another pamphlet, Aesop at Turnbridge, printed by Elizabeth Whitlock, included in this volume. These two women likely had some sort of dialogue in print between them, from opposite sides of the political spectrum.