In the Conservation Lab

Preserving the Gwendolyn Brooks collection involves some unique challenges due to the materials and the nature of the collection. Poor quality, twentieth-century materials (such as acidic papers and degrading plastics) are one thing, but the bigger challenge comes when we try to preserve and capture Brooks’ creative process, collecting habits, and her ways of taking care of her collection. The conservator's work on this project has been about finding a balance between saving Brooks’ originality and reducing the risks and damages to the material during use to ensure long-term access to this collection, as they do not always go hand-in-hand.

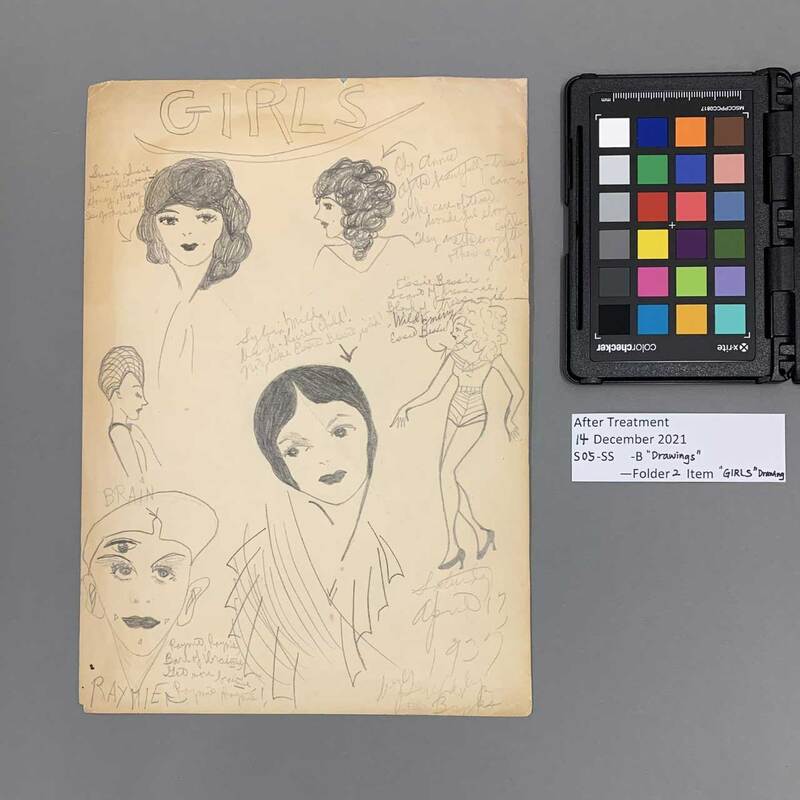

This project has been teamwork all along since the collection consists of a wide range of materials in various conditions with special needs. Digitization Services (DS) and Conservation keep an open conversation to decide which comes first—digitization or conservation—for each case. We discuss the issues through emails, regular virtual meetings, and in-person meetings as needed. The two major factors for the decision-making are: 1. If the conservation treatment will significantly change the original nature of the object; and 2. If the current condition of the object limits access to the contents or endangers the object’s integrity when handled. This is because digitization is not merely capturing the contents of the writings but also preserving how Brooks kept her papers, organized her family photographs, tried to salvage a falling-apart notebook, and so much more. Here are some examples of different issues that we have had to consider:

Example #1—Red Photo Album:

This album has been fully digitized before any conservation treatment. The conservation of the album is very likely to change the original nature of the photo album and its arrangement, so we wanted to capture that before altering anything further, especially since the individual photographs were not at great risk of further damage during the digitization process.

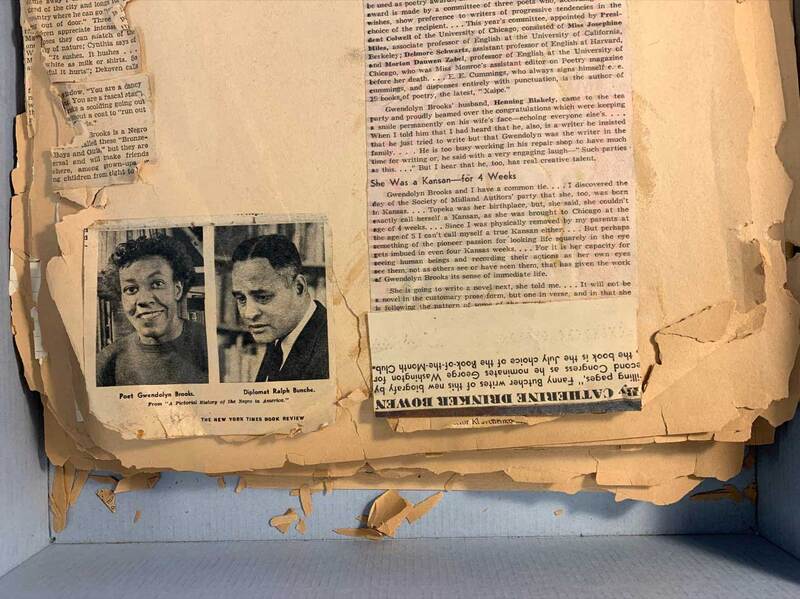

Example #2—Black Scrapbook:

DS started digitization of the scrapbook but had to put it on hold as some of the pages included extremely brittle newspaper clippings with folds. After DS digitized as much as they could without damaging the pages too much, the scrapbook was sent to Conservation Lab for treatment. The remaining pages will be scanned after the item is treated for safer handling.

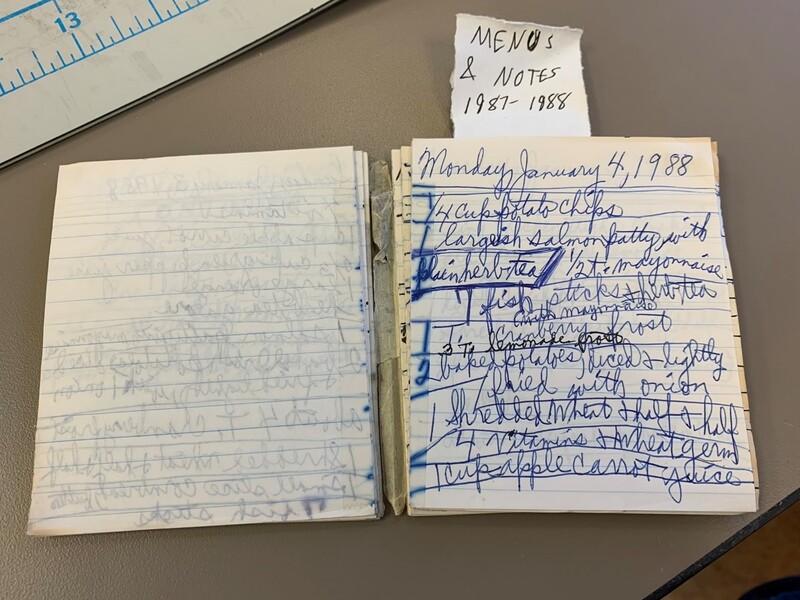

Example #3—Taped Notebook:

The notebook came to the lab first for mold remediation. After the cleaning, Yungjin made enclosures for the spiral notebooks and inserted polyester sleeves to the pages with tapes (to prevent them from sticking and affecting the adjacent pages in the future). Then she encountered a small notebook with tapes in the gutter (“Menus & Notes 1987-1988"), likely done by Brooks to keep the pages together. To isolate the taped pages from the others, it was necessary to separate them out and individually house them in polyester sleeves. Since the rehousing will change the original binding of the notebook, we thought it would be best to digitize it before moving on.

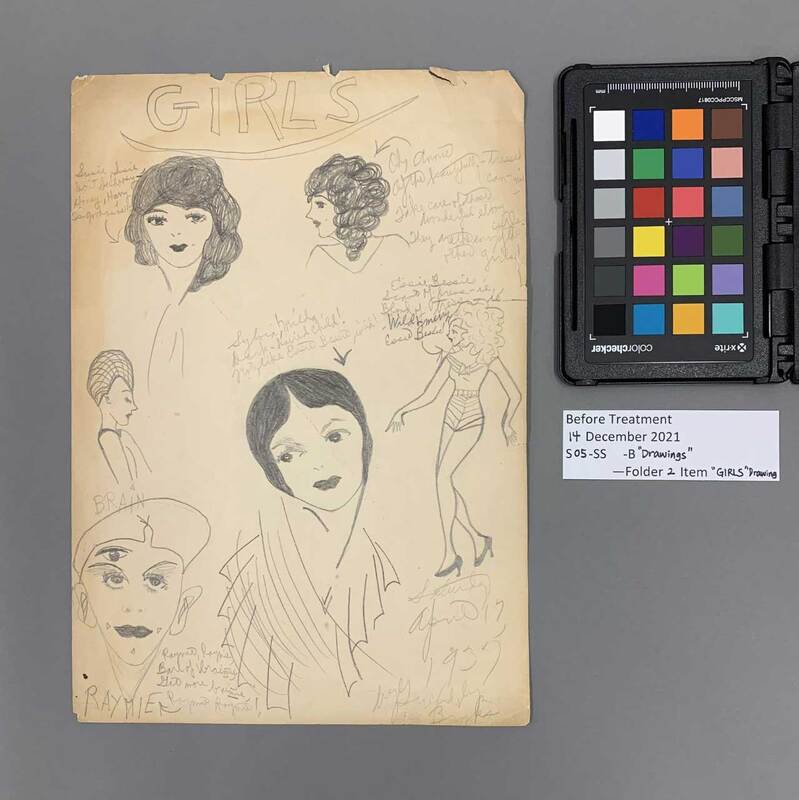

Example #4—Tear Mending:

One of the most prevalent issues in this collection is tears, considering the often poor-quality acidic wood pulp paper-based materials. In Yungjin's usual conservation practice, she would mend the tears whenever she spotted them because they are a risk for further damage when handled. However, instead of automatically mending the tears, she went through one extra thought process for this project: can the item be handled safely by DS when scanning? If yes, simply place the item in a polyester L-sleeve, so that the item can be handled safely as is and DS staff can pull out the item from the sleeve for digitization. If not, mend the tear and then place the item in a sleeve. This was due to the large scale of the project and to keep the workflow efficient so that all fragile materials can receive the minimum protection at least.

Tears treated (before treatment)

|

Tears treated (after treatment)

|