Exhibit Contents

Scandal, Sex, and Romance

Jane Austen held her heroes to a higher standard than that of “gentleman.” Many of Austen’s most beloved heroes are considered “good” Regency gentlemen not because of their wealth, but because of their self-education, care for others, and kind, often more equitable approach to those with fewer resources. (Darcy, Knightley, Colonel Brandon, Edward Ferrars, Captain Wentworth, Edmund Bertram). She provided counterpoint characters as examples of what not to do, even when contemporary social mores allowed for (and sometimes encouraged) activities like gambling and fornication. Austen’s “bad boys” tend to squander their fortunes, lack motivation for their own occupations, enter into inappropriate intimate relationships, or directly cause harm to others through inaction or indifference (Wickham, Willoughby, Robert Ferrars, Tom Bertram, Henry Crawford). Distinguishing between a man who initially presents as a gentleman but is a poor candidate for marriage and stability, and a good man (self-made or otherwise) who demonstrates personal character despite not being completely fashionable, is crucial for Austen’s heroines.

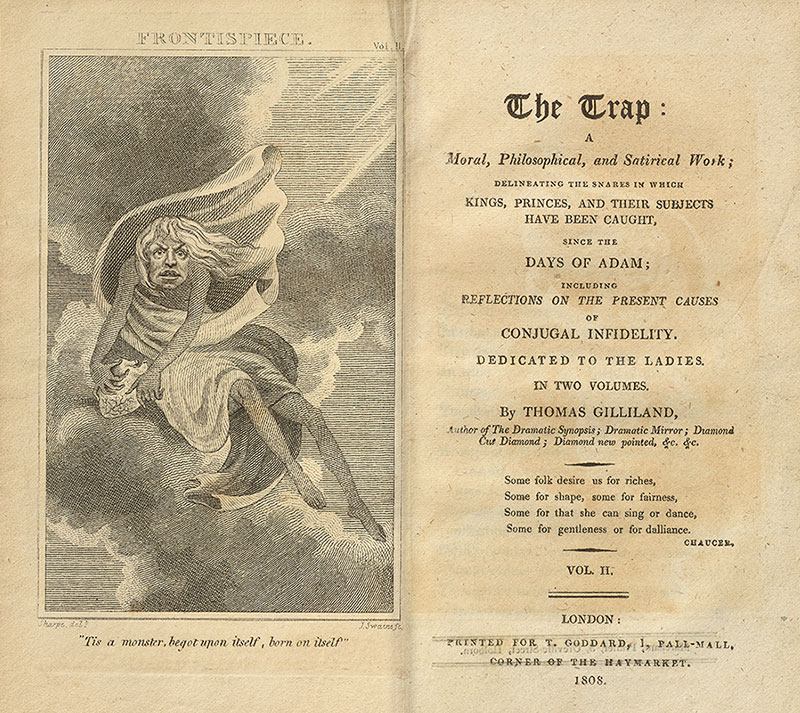

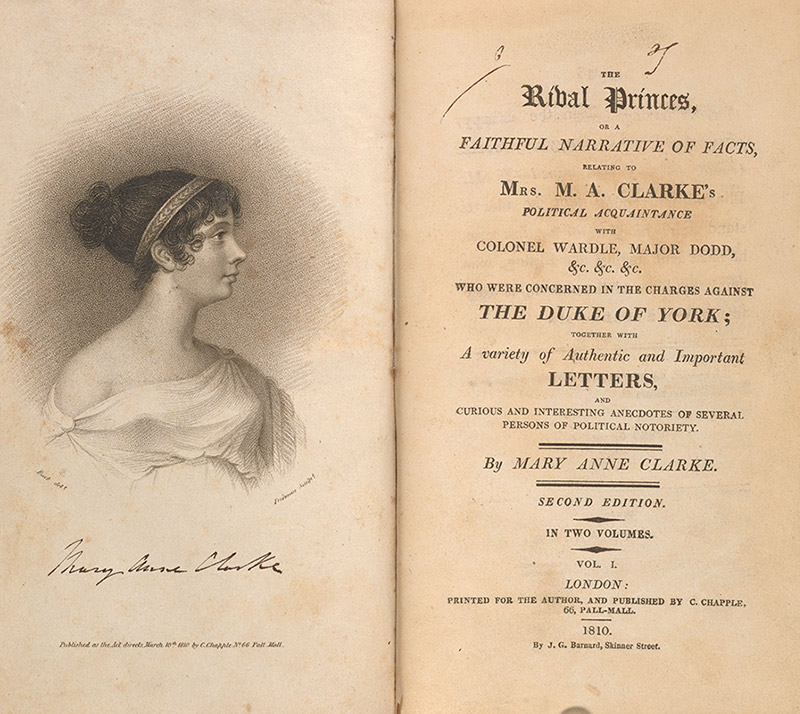

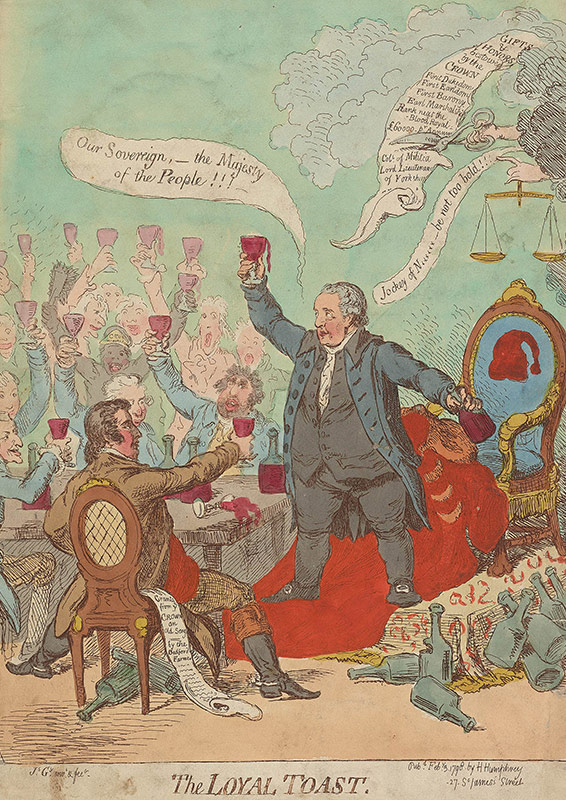

While we may think of the Regency period as being excruciatingly genteel and emphasizing the utmost correct manners and etiquette, sex-related scandals abounded. While women in good society (le monde) and more scandalous society (le demi-monde) were scrupulously guarded from one another, gentlemen moved back and forth, with varying levels of discretion. Works on this page include the high social sticklers of Almack’s (who once denied admission to the Duke of Wellington because he wore trousers, which they had recently banned) to some of the greatest scandals of the age: George IV’s attempt to divorce Queen Caroline, the illicit relationship between the Duke of York and Mrs. Clarke, and the publication of Harriette Wilson’s Memoirs.

Works Included

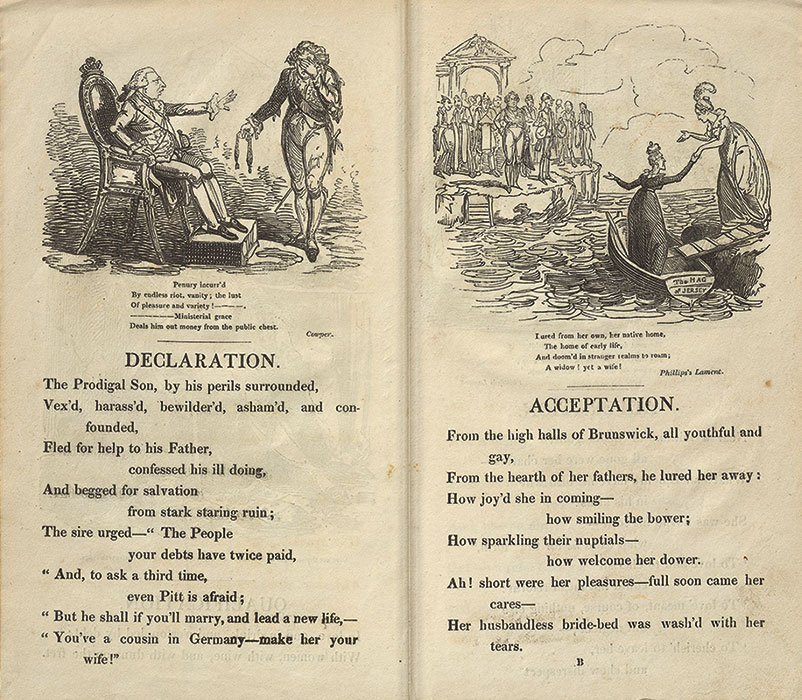

The Queen's Matrimonial Ladder

A satire, in verse, on George IV in defense of Queen Caroline. "All drawings for this publication are by Mr. George Cruikshank"

Call number: 941.074 T763 v.2

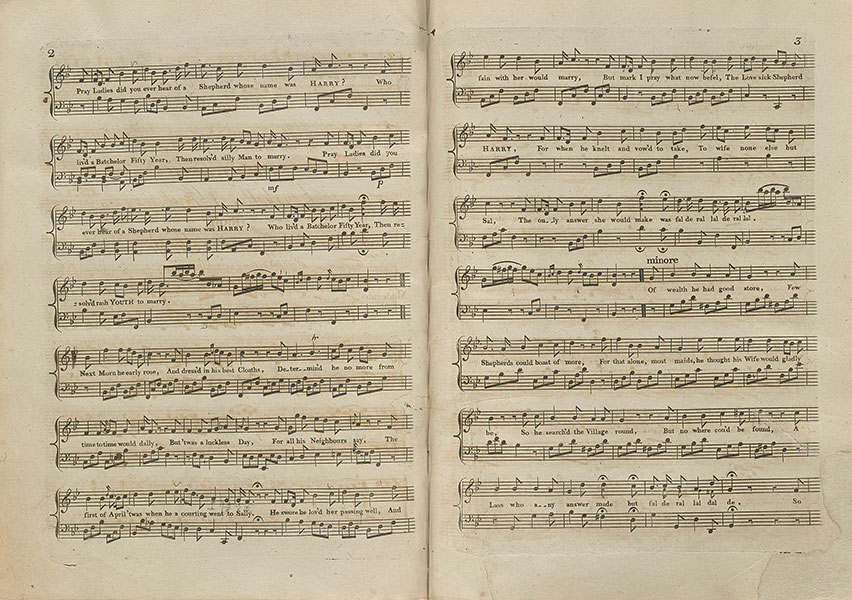

"The sweets and sours of matrimony.” In Braham’s music in the favorite opera False alarms

Call number: Q. Fraenkel 690

Glenarvon

Caroline Lamb’s Glenarvon was a thinly veiled, bestselling roman-à-clef about the ill-fated brief romance between Lamb and Lord Byron.

Call number: 823 L165gℓ

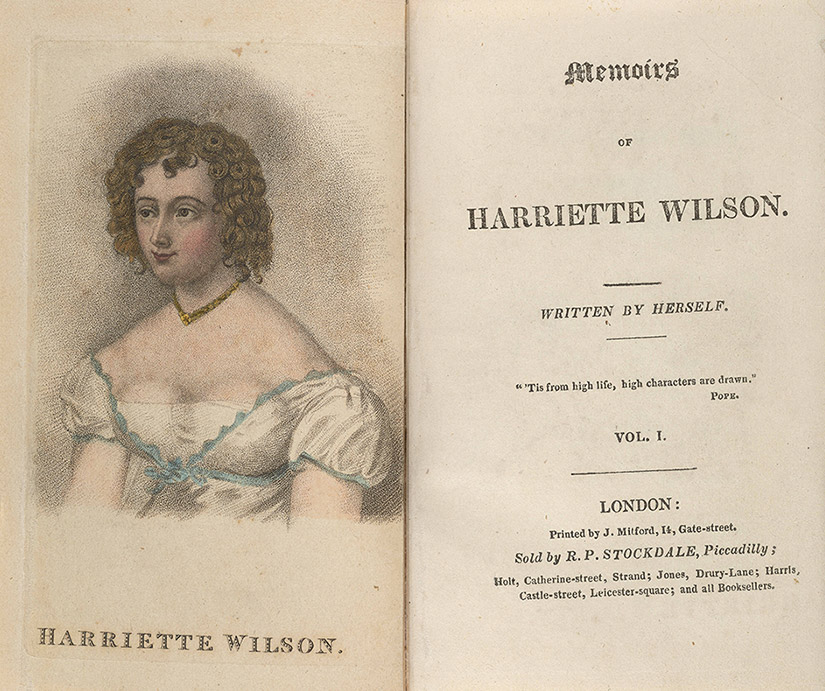

Memoirs of Harriette Wilson

This is likely a pirated edition with a false imprint by Benbow and Mitford following the 1825 J.J. Stockdale publication. The publication of Wilson’s Memoirs was one of the biggest scandals of the day; after years as a courtesan, she wrote to each of her previous paramours to tell them of the publication of her Memoirs. Each ex-lover (including the Duke of Wellington) was granted the opportunity to not be named directly in the memoirs in exchange for two hundred pounds (which is about ten thousand pounds now).

Call Number: B. W7481w1 1825